Alexander Wacker

On July 8, 1918, Alexander Wacker (2nd from left) received King Ludwig III of Bavaria (4th from left) in the new factory in Burghausen. For his achievement in setting up the plant, Alexander Wacker was granted an aristocratic title by Ludwig III.

Read time: approx. MinutesMinute

A Start-Up Entrepreneur in the Imperial Age

Alexander Wacker wasn’t a chemist or an engineer. He was a qualified textile merchant. And yet he, who died 100 years ago, on April 6, 1922, became one of the pioneers of German industry – first in the electrical engineering sector, and then in the electrochemical sector. He began his life’s greatest achievement in 1914, when he was 68 years old. Today, 100 years after his death on April 6, 1922, his creation, Wacker Chemie, is among the leading suppliers on the world market for all its main areas of business.

When Alexander Wacker registered Wacker Chemie at the Traunstein Commercial Register on October 13, 1914, he was 68 years old – an age at which most people have already retired, not only today but back then, too. In addition, he had just suffered a great loss: his son Franz Alexander, a chemist he had wanted to establish as his successor, died. He was just 31 years old. Plus, World War I had just broken out in Europe – hardly an ideal time to open a business.

Nevertheless, Alexander Wacker who already looked back on a long career, in his own company and others, staunchly persevered with his plans. What motivated him to rise to new entrepreneurial heights at the end of his life, and found a company that has passed the 100-year milestone? As is often the case: The clue lies in his childhood.

Commercial apprenticeship in far-off Schwerin at the age of 15.

Eight months before Alexander Wacker was born, his father died of tuberculosis. His mother remarried. The young Alexander was raised by his maternal grandmother and aunts, but maintained regular contact with his mother. Alexander Wacker would gladly have gone to university, but money was tight and the family took him out of school at the age of 15. In1862, in far-off Schwerin, he began a commercial apprenticeship as a textile merchant – a trade that neither suited nor fulfilled him.

Presumably, these early experiences, not uncommon at that time, spurred on his entrepreneurial ambition. The honors bestowed on him in the latter part of his life, including honorary doctorates from the universities of Heidelberg and Göttingen and an aristocratic title must have given him satisfaction.

Alexander Wacker

Generators in the Muffat plant, a power plant built by EAG in Munich.

The founding of the German Empire in 1871 marks the start of the so-called founding years – decades of rapid industrial innovation and expansion that made Germany the world’s second-largest industrial power after the United States by 1914.

Alexander Wacker’s entrepreneurial years also began during the founding years. He established a silk manufacturing company in Kassel in 1872. Three years later, in 1875, he took over a machine trading company in Leipzig. And In 1877 he met Sigmund Schuckert, a precision engineer. This meeting changed the course of his life. From then on, Wacker sold the dynamo machines and electrical equipment his new companion manufactured in a small workshop in Nuremberg with just 28 employees.

Then Alexander Wacker’s career really took off. In 1884 he became commercial head of the Schuckert factory and moved to Nuremberg. Four years later, Schuckert made him a shareholder of his company, one of the pioneers of electrification in Europe in the late 19th century, much like Siemens and AEG.

He set up sales offices across Europe for Schuckert: he must have been a talented salesman. “Wacker was unbeatable in acquisition,” said Georg Wilhelm from the large rival company Siemens.

The founding years during which Alexander Wacker became great and wealthy, were extraordinary, dynamic, breathtakingly fast-paced times, comparable to today. Between 1871 and 1914, a rapidly expanding industry radically changed the world – with dynamos and fertilizers, automobiles and telephones, synthetically produced pharmaceuticals and, sometime later, the first plastics. Electrical engineering, mechanical engineering and the chemical industry created completely new markets, laying the foundations of a new world – just as information technology, the Internet and biotechnology are doing today.

At the turn of the last century, people like Werner von Siemens or Andrew Carnegie, were the Jack Ma, Elon Musk or Steve Jobs of modern times. Or, for that matter, Alexander Wacker. Like a start-up entrepreneur of the imperial age, his career path took him from city to city and company to company at a rapid pace. Eagerly he embraced innovations and experimented with a number of sectors. He and Schuckert benefited from the speed at which worldwide economic networks grew at the end of the 19th century – another parallel to our times. This pace was only reached again a century later with the surge in globalization following the opening of the Eastern Bloc between 1989 and 1991.

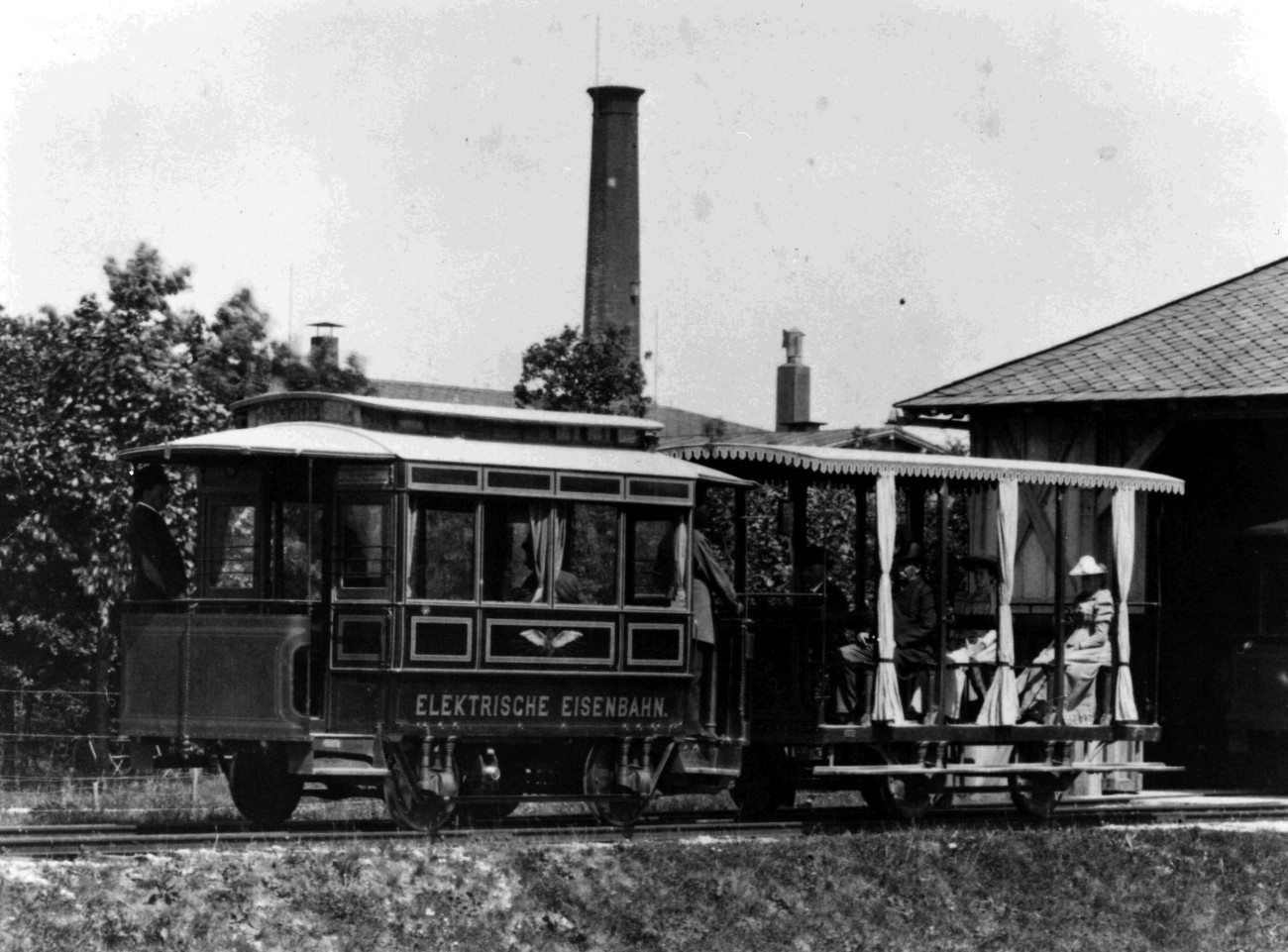

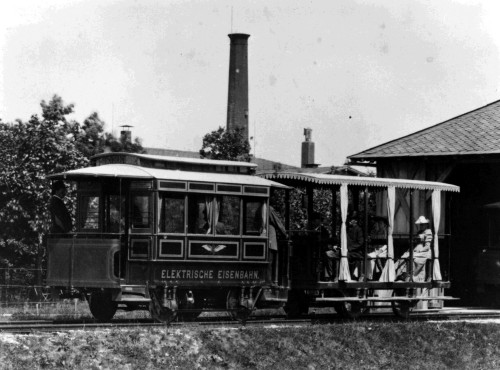

Under the commercial management of Alexander Wacker, Schuckert built the first electric tram line for the city of Munich in 1886, and the first electric power plant for the city of Lübeck in 1887. In 1892, Sigmund Schuckert retired from the company he had founded due to a nervous condition. The partners then transformed Schuckert-Werke into Elektrizitäts-AG, or EAG, also based in Nuremberg. The general director was Alexander Wacker. By the turn of the century, the company’s workforce numbered 8,500. Earnings skyrocketed – from 56,000 German mark in 1880 to 46.5 million in 1898.

The Schuckert plant supplied an electric tram for the city of Munich. It went into operation in 1886.

Carbide factories in Bosnia, Switzerland and Norway.

The electrical and chemical industries initially went separate ways in the founding years. As time went on, they increasingly moved in tandem, and each benefited from the other’s progress. Gifted with astute business acumen, Alexander Wacker foresaw this development. Directly or indirectly, he acquired various carbide factories in Bosnia, Switzerland and Norway, among others, where calcium carbide was produced using large amounts of cheap hydro-electric power. Alexander Wacker’s initial idea was to process this carbide into acetylene and then sell it as illuminating gas for city lighting. However, this did not pan out. The electric light bulb outrivaled the gas light and soon became the default in the private sector, quashing the market for acetylene.

This setback – possibly the biggest in his career – left Alexander Wacker undeterred. He retained the carbide factories and the laboratory – later to become the Consortium – when he sold EAG to Siemens & Halske in 1902. Even before the sale, he had resigned as general manager and moved to the company's supervisory board – a position he never warmed to.

What to do with the stockpile of carbide? When he founded the Consortium for the electrochemical industry in 1903, Alexander Wacker’s instruction to his chemists was along the lines of “Get rid of the carbide!”

Alexander Wacker in different phases of his life: as a commercial apprentice in Schwerin in 1863, as a young entrepreneur in Kassel in 1874, as General Director of EAG in 1901 and in later life.

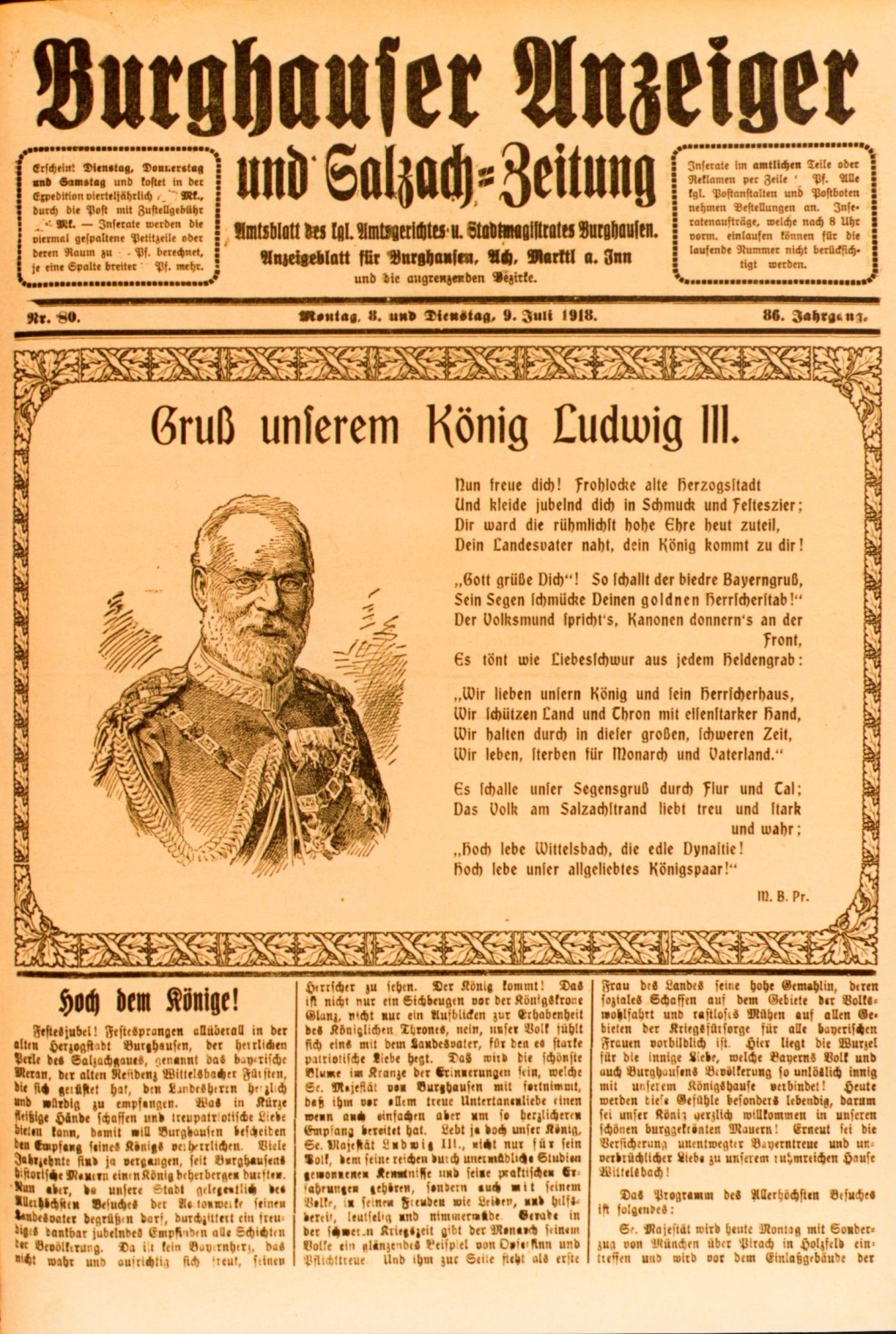

The Burghausen newspaper published an extensive report on the visit from the last Bavarian monarch.

Around a dozen of the Consortium’s chemists, technicians and assistants spent this interim period lasting over ten years working on finding commercially viable uses for carbide and acetylene. Alexander Wacker wasn’t a chemist, but he was a patient man. He understood that systematic research is a prerequisite for commercial success – a principle that he also applied in the company that later became Wacker Chemie. He was able to afford this long phase of groundwork in the Consortium because, despite surplus production, his carbide factories had a stable economic basis: they also produced ferro and silicon alloys, which were needed for welding and steel production, among other things.

Between 1903 and 1914, the Consortium became the scientific hub of the future Wacker Chemie. Its chemists filed dozens of patents, some of which were licensed to other companies, while others, such as chlorinated hydrocarbons, remained pillars of WACKER’s business until the 1990s. The first being the 1st WACKER Process for manufacturing acetylaldehyde, which was further processed to synthetic acetic acid and later to vinyl acetate – basically the “big bang” for the WACKER POLYMERS business division’s highly successful VINNAPAS® range.

What Alexander Wacker still needed in his adopted home in southern Bavaria was a large electrochemical plant to turn theory into practice – the Consortium’s patents into operational production. In 1913, Burghausen, a remote fairly rural town at the time, was selected, because the elevation gradient of around 70 meters between the Alz and Salzach rivers would enable the construction of a hydroelectric power plant by means of a canal. And chemical production needs vast amounts of electricity.

But the onset of the First World War in 1914 put a stop to the construction work on the Alz canal and the WACKER plant until the attention of the War Ministry in Berlin was drawn to a process developed at the Consortium for the production of acetone from acetic acid. Acetone was the base material used by Bayer in Leverkusen to manufacture artificial rubber for sealing the accumulators of submarines. Suddenly, the WACKER plant was considered important for the war effort, and it all had to go very quickly. On December 7, 1916, the first industrial production of synthetic acetone in the world went into operation. To mark this milestone, King Ludwig III of Bavaria conferred an aristocratic title on Alexander Wacker in 1918.

A few months later, the war was lost, and the Kingdom of Bavaria was history, along with the German Empire. And after 1918, no one in Germany needed acetone for submarine construction – 60 percent of sales were lost in one fell swoop.

Enduring legacy

Privy Councilor Dr. Alexander Ritter of Wacker, as he was then allowed to call himself, once again faced an enormous challenge in the last four years of his life. He had to bring about what we’d term a transformation today: the transition from military to civilian production. By then 72 years of age, Alexander Wacker tackled the task with great resolve and also set about settling his affairs. In 1920, he transferred his Wacker Chemie shares to a family holding company – an arrangement still in place today, giving the company continuity and stability.

In 1921, the family sold half their shares to Hoechst. Alexander Wacker urgently needed capital to cover the rapidly rising costs of the Alz Canal construction. This old-school “joint-venture” was a successful partnership for many decades. In 2005 and 2006, shortly before Wacker Chemie AG’s IPO, the family led by Dr. Peter-Alexander Wacker, a great-grandson of Alexander Wacker, bought back the Hoechst shares.

When Alexander Wacker died on April 6, 1922, just before his 76th birthday, he secured his last and most enduring company by establishing the new family-owned holding company. And in Burghausen, a remote town in southeastern Bavaria, he created a groundbreaking full-scale chemical production plant that now ranks among the top three global suppliers in all its main business areas and operates large integrated production sites in Germany, the USA, China and Korea. Alexander Wacker’s aptitude for innovation and developing new technologies and business fields is still very much alive and well a hundred years later in the company he founded.

This industrial pioneer’s “start-up” gene dating back to the far-off imperial age is part of Wacker Chemie AG’s DNA. The entrepreneurial tradition that Alexander Wacker established lives on unabated as the founder’s family continues to cultivate this heritage going forward.

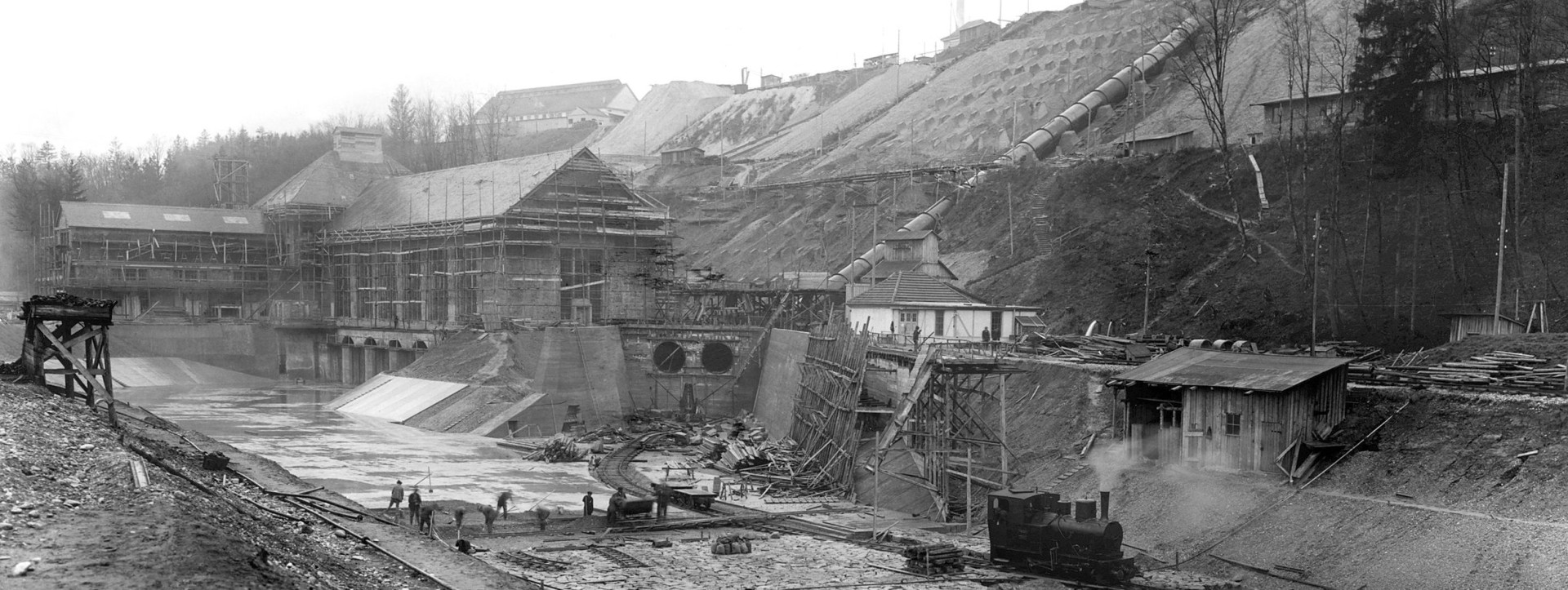

During the years of construction, the site in Burghausen consisted of the acetone factory, the mercury oxide electrolysis facility, the main building, workshops and the boiler house.

Construction of the Alzwerke hydroelectric facility in Burghausen: Alexander Wacker’s vision of chemical production with hydro-electric power was implemented in his own plants.