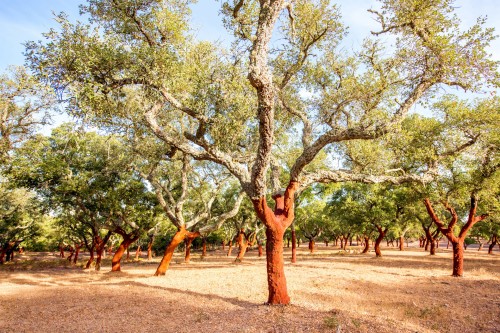

100 to 200 kilograms of cork

can be harvested from an oak tree over its lifespan. Corks are harvested every nine to twelve years once the layer of cork has become 2.7 to 4 centimeters thick, sometimes slightly more often in a favorable (warm) climate. A cork oak can be harvested a total of five to ten times.

Jul 26, 2021 Read time: approx. MinutesMinute

Silicone: the Key to a Gentle Pop

For many, wine and champagne are the epitome of indulgence and joie de vivre. But first you have to get the cork out of the bottle. If it’s made of untreated cork, you might have a challenge, but with a certified, solvent-free silicone coating, the cork will pretty much slide right out.

Schiller himself appreciated the value of the cork so much that he penned the following lines in its honor: “What reverence is due the world’s Creator, / Who when creating the cork tree graciously also invented the cork.”

The structure of stoppers made of pure, natural cork, however, is not uniform, often containing flaws and tiny channels. Most importantly, bottlers have a difficult time forcing untreated corks into bottles and consumers have an even more difficult time pulling them out. To help corks slide more readily, retain their seal and not leave behind any bits or cloudiness in the wine, manufacturers treat them with a variety of lubricating and impregnating agents; paraffin waxes have long been used for this purpose, despite their various disadvantages.

Freshly harvested cork oaks in Portugal: roughly half of the world’s annual production of cork comes from here.

In recent years, silicone fluids, too, have become established for wine corks, though not for sparkling wine. “Silicone fluids shouldn’t be used for corks in bottles of sparkling wine, because they have a defoaming effect,” says Dr. Christian Ochs, a chemist who heads up an applications laboratory for WACKER SILICONES in Burghausen. Another option for improving natural cork is to coat it with silicone rubber, which, unlike silicone fluids, has no defoaming effect.

“Our ELASTOSIL® E 6 N CSC silicone rubber is suitable for wine-bottle corks as well as for those used in sparkling wine and liquor bottles – regardless of the type or quality of the cork stopper.”

Dr. Christian Ochs, Head of Technical Marketing, Industrial Solutions, WACKER SILICONES

Making Wine Corks

1 The harvested cork is kept in stacks for over six months in order to acquire the ideal moisture content for processing.

2 Cutting the plank wedges

3 Sorting the cork planks

4 Boiling and stabilizing: cleaning the cork and extracting water-soluble substances increase its thickness and reduce its density, making the cork softer and more elastic.

5 Selecting and splitting planks, punching the corks: the edges of the planks are prepared, their corners trimmed and the planks sorted according to quality criteria (thickness, porosity and appearance). The planks are ultimately split into strips somewhat wider than the length of the corks to be manufactured, which are then punched from the strips.

6 Cork selection: the surfaces of finished corks are automatically scanned in order to separate the corks into different grades.

7 Washing/disinfecting

8 Branding: the brand is applied to the finished product.

Not All Cork Is Created Equal

“Our ELASTOSIL® E 6 N CSC silicone rubber is suitable for wine-bottle corks as well as for those used in sparkling wine and liquor bottles – regardless of the type or quality of the cork stopper,” Ochs stresses. And indeed: not all corks are created equal. The highest grade of cork is one that has very few pores once it has been punched from the bark of cork oaks. Corks of that quality are mostly reserved for superior wines, which are intended to age in the bottle for long periods of time.

When it comes to average-quality corks, which might have many cavities or an irregular structure once punched out, manufacturers have a trick up their sleeve: they fill the pores with a blend of cork dust and binders. This filling makes the cork more durable and improves its contact with the glass.

Cork cannot be harvested until the tree is roughly 25 years old. What’s more, the tree does not yield the quality needed for bottle stoppers until the third harvest

What are known as agglomerated corks represent a lower grade of quality: here manufacturers use leftover bits from cork production and compress them together with a binder. A variation on agglomerated corks is the technical cork, which has an agglomerated cork body with natural cork disks glued onto it – this primarily serves to keep the surface that comes in contact with the alcoholic beverage as natural and durable as possible.

“For cork manufacturers, the universal applicability of ELASTOSIL® E 6 N CSC is a big advantage, because it allows them to use the same silicone rubber on multiple production lines for a wide range of corks. That simplifies logistics and cuts administrative costs,” explains marketing manager Martine de Schmidt-Camilleri.

Corks are coated in rotating drums resembling large washing machines, where they are tumbled along with the silicone rubber for at least 20 minutes. This evenly distributes the silicone elastomer formulation over the corks. “If the silicone is going to do a good job of coating the surface and cavities of the corks, it can’t be too thick – its viscosity has to be low, in other words,” Ochs explains. And that is precisely the hallmark of ELASTOSIL® E 6 N CSC: the viscosity of this silicone rubber product is low, despite containing no solvent.

Vulcanization starts even before the manufacturer takes the corks out of the drum, as the macromolecules within the rubber react chemically with each other to form larger, crosslinked units. These units are no longer as free to move relative to each other as the original molecules, causing an extremely thin, elastic coat to form on the cork. In addition to making the surface of the corks feel pleasantly silky and smooth, the silicone also repels water thanks to its hydrophobic properties. Crosslinking – a process that releases small molecules such as acetic acid – proceeds best at elevated humidity and a temperature between 25 °C and 35 °C.

“ELASTOSIL® E 6 N CSC is universally applicable, which allows cork manufacturers to use the same silicone rubber on multiple production lines.”

Martine de Schmidt-Camilleri, Marketing Manager, WACKER SILICONES

All of the Necessary Approvals

“It goes without saying, of course, that the cured silicone coating will not introduce any harmful substances into the product,” Ochs emphasizes. Regulations in Germany, France, Spain, the EU and the US hold that ELASTOSIL® E 6 N CSC is suitable for contact with food. In this traditionally minded industry, however, another judgment carries almost more weight: the Comité Champagne trade association of the Champagne region of France has certified the WACKER silicone rubber as, among other things, a coating on corks used for true Champagne.

In addition, a major cork manufacturer has studied the use of the solvent-free, silicone rubber coating, asking its experienced taste testers to determine whether it has any influence on the color, aroma or flavor of the beverage with which it comes into contact. For comparison, the testers tasted the same wine sealed with traditionally coated corks and aged for exactly the same amount of time, such as three months or a year. “These tests were a success for our silicone rubber coating,” reports Schmidt-Camilleri, which gives her hope for opening up the market.

Barrique is the French word for the oak barrel traditionally used for storing wine until it has aged sufficiently.

Corks coated with silicone rubber are easier to remove from the bottle.

And that market is not a small one: 200,000 metric tons of cork are harvested each year, roughly half of which comes from Portugal. But not all of that cork goes into the production of cork stoppers. After all, demand for the material is also high in applications such as flooring, thermal isolation and shoes. Still, the vast majority of cork is used for manufacturing some 13 billion stoppers for (sparkling) wine bottles each year.

The only way the cork business can work is by means of an intergenerational contract of sorts: cork growers do not plant cork oaks for themselves – they plant them more for their children and grandchildren. Cork oaks in Mediterranean countries first need to grow for 25 years before their bark is stripped for the first time. This “virgin cork” is too brittle and too hard to be made into natural corks, however. The next harvest will not be for another nine to ten years – and so on for every subsequent harvest. The quality of the cork is not optimum until after the third harvest. In other words, some 45 years pass from the time a cork oak is planted until it first yields perfect natural cork. Compared to that, giving the natural material the right properties by coating it with silicone rubber happens in the blink of an eye.

Crosslinking Mechanism for Silicone Rubber

Typical Properties of One-Part, Room-Temperature-Vulcanizing Silicone Rubber (RTV-1)

A one-part system:

+ Easy to use

+ Little investment for processing equipment

+ Cures at ambient humidity

+ Curing process is not sensitive to other substances

+ Excellent adhesion to a variety of substrates

+ Robust, user-friendly formulations

- Releases acetic acid as a byproduct (5%), ventilation required

Condensation reaction: a chemical term denoting a substitution reaction in which two molecules bond together to release a simple, low-molecular-weight material. While this material is most often water, the product released can also be ammonia, carbon dioxide or hydrogen chloride. Condensation reactions form the basis for the production of many different polymers.

Mrs. Martine de Schmidt-Camilleri

Industry Manager

Construction Solutions

+49 89 6279-1384

martine.de.schmidt-camilleri@wacker.com