Replicas of the most significant sculptures from antiquity to modern times

Mar 01, 2018 Read time: approx. MinutesMinute

Copies from the hand of a master

One of the best in his profession, Arnaud Briand has a contract with the French association of national museums to create plaster copies of the most important sculptures in art history. And for his reproductions of originals he uses silicone elastomers from WACKER.

Modern public housing, a dozen construction sites surrounded by cranes, and plots overrun with weeds – this is what the neighborhood looks like around the “Ateliers de moulage.” This studio, which belongs to the national museums of France and where replicas of the most significant sculptures from antiquity to modern times are made directly from the originals, is housed in an unprepossessing, functional metal building from the 1990s in Saint-Denis, Paris – just a few hundred meters from the well-known soccer stadium. While this suburban location may jar with the images we commonly associate with stately French museums, the disconnect quickly fades as soon as you walk through the doors of the studio.

Inside, immediately next to the breaker box and the fire extinguisher, suggestive necklines lure visitors over to three red-white-and-blue sculptures of Marianne, the national symbol of France. In the spacious lobby, which serves as both an office and a reception area, well over 250 busts and miniatures are stacked up to the ceiling on simple wooden shelves. Eyes gazing into the distance, hands folded gracefully, muscular bodies outstretched. A desk with a computer is all but invisible behind a monumental statue of a reclining three-meter-long Greek goddess. The head of a Madonna serves as a bookend on the back shelf; boxes of index cards form the foreground to an ancient Roman relief; and immediately next to that, the tender face of a child shares the cramped shelf space with a used coffee cup.

The first step in making an impression is to coat the original sculpture with a layer of polyvinyl alcohol to protect it from being damaged during the process. You always get the first mold from the original, says Briand.

“There are a lot of amusing coincidences around here. Entirely unrelated objects end up sharing the same space,” says Arnaud Briand with a laugh. The 43-year-old Frenchman is a mouleur statuaire – a moldmaker and plaster-caster, in other words – and has been authorized to refer to himself as a Meilleur ouvrier de France since 2015. This prestigious, lifetime title – MOF for short – is an honor bestowed in France on unusually gifted artisans who have undergone an exacting test and are esteemed master craftsmen. “The title is something of a holy grail,” explains Briand, who took the challenge in the “Decorative Plaster Sculptures” category and succeeded. “There are only four or five MOFs in France with this particular area of specialization. And here in the studio, I’m the only one.”

“Now, when I organize my ‘ingredients’ for making an impression of a piece, I follow the same strategy I used for managing deliveries in the kitchen. You have to be really well prepared.”

Arnaud Briand, moldmaker and plaster-caster, Meilleur ouvrier de France (2015)

Arnaud Briand in his studio

Many of the copies at the “Ateliers de moulage” are over 200 years old and in better shape than the originals. Their value lies in the fact that they bear testimony to hundreds of years of the art of sculpting.

Intuition required

Briand began working in Saint-Denis in 2009 when the renowned studio operated by the Louvre and the French association of national museums (RMN) was contracted to replace the sculptures in the gardens of Versailles with more weather-resistant cast-resin copies. “I had worked with a lot of casting resins for my previous employer, so I had a fair bit of experience with the material,” explains the Parisian, who took a non-traditional path to his profession, discovering his passion for casting only at the age of 30. Prior to that, he had spent ten highly successful years in catering. When his then boss was forced to close his restaurant, Briand had to make a choice: either open his own bar or change careers. A three-month internship eased the decision for him. “My years in catering help me in my work today too,” says the master craftsman. “Now, when I organize my ‘ingredients’ for making an impression of a piece, I follow the same strategy I used for managing deliveries in the kitchen. You have to be really well prepared.”

And that preparation shows: Briand’s work bench has everything on it he needs, all carefully laid out and waiting to be used. Kitchen utensils such as pastry scrapers, knives and ladles are positioned next to numerous spatulas, a wire brush, scissors, emery paper and an electronic scale. Large tools like saws and electric drills hang on the wall where they are readily accessible. The windowsill is strewn with plastic containers full of brushes in all shapes and sizes. An old olive jar is filled with mineral spirit. “This spirit is exceptionally compatible with silicone. Just the thing for cleaning brushes.”

The original ensures the best quality

Briand reaches for a pack of blue disposable gloves and begins working on an 18th-century bust about 30 centimeters high. “You always get the best mold from the original. But we have plaster molds here that are nearly 200 years old and, in some cases, are in better shape than the original sculpture,” he explains as he brushes a protective coat of polyvinyl alcohol onto the bust.

While that layer dries, Briand blends the silicone for the first coat. He places a bucket on the scale and uses a plastic cup to measure out the ingredients – which he appears to do just by feel. The muscular Parisian then stirs the mixture with a pastry scraper, constantly checking its texture. “While I do have a book with all the formulations, what I’ve learned from experience is even more important,” says Briand. “Because many factors can play a role, like room temperature. It’s a little cool in the studio today, for example. I have to take that into account.”

When he uses brand-new products, Briand initially sticks to the recommended proportions provided with the product. After that, however, he feels it is his job to perfect the formulation. “Trial and error is the only way to bring out the best in a product. I’m really curious, and I like experimenting, because it shows me the limitations of a product and indicates what will work and what won’t.” And afterward, he’s happy to share his experience with the manufacturers. He also tells them what he’d like.

Right now Briand is trying out WACKER’s new curing agent for its ELASTOSIL® M silicone rubber compounds, which are distributed in France by ABYLA (Gazechim Group). NEO is a catalyst containing no organotin compounds, and the corresponding NEO booster makes it possible to cure relatively thick layers of material – together with silicone rubber, an excellent combination for making a mold quickly.

Preparing and organizing your tools well is an indispensable step in creating copies if the process is to go smoothly.

“While I do have a book with all the formulations, what I’ve learned from experience is even more important.”

Arnaud Briand, moldmaker and plaster-caster, Meilleur ouvrier de France (2015)

“I see this product as a major advance,” Briand says. After all, when he and his colleagues worked on their contract in Versailles, they processed 120 kilograms of silicone in just one-and-a-half weeks. And even in the case of a small bust like the 18th-century head he’s currently working on, he still uses two to three kilos, because he will apply up to four layers of material to the sculpture.

In each new layer of silicone, the master moldmaker slightly modifies the texture and composition, adding a few drops of a catalyst or a thickener here and there. “You get a better result if you work with a really thin silicone for the first two layers and with thicker material after that.”

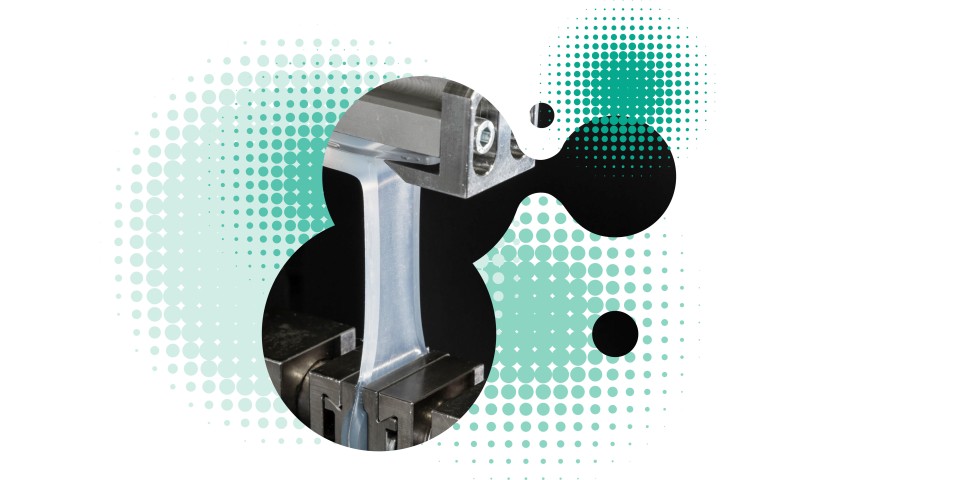

When using a casting process to make a mold, the individual parts first need to be securely bolted together before casting can begin. Shown here is a small-scale copy of a bestseller: the Nike of Samothrace.

Silicone is now dripping continuously onto the work bench. Again and again, Briand uses scissors to cut off the drops and carefully pats the surface with his little finger to monitor the drying progress. He allows about a half hour to elapse between each layer. The final layer is applied along with a glass fiber mesh, which partially envelops the previous layer.

For difficult spots around the eyes, mouth, ears and nose of the sculpture, Briand uses a syringe to apply a rather viscous silicone, which he has optimized with a thickening agent. This smooths out irregularities to produce a homogeneous surface he then carefully blots with a damp sponge. “That destroys the air bubbles that form when I apply the silicone.” The back of the sculpture has already been sufficiently reinforced with a final layer of silicone rubber. For this last layer, he has to stay focused and work fast – it hardens in just five minutes.

Briand primarily uses two grades of silicone: ELASTOSIL® M 4514 is his choice for preparing skin molds, as they are known. By adjusting the concentration of the curing agent or by adding a thickener, he can also use this compound for controlled, vertical molding processes. And for casting what are known as block molds, he uses ELASTOSIL® M 4630 A/B.

Using a casting process to create silicone molds is technically very demanding. “You can’t make any mistakes during casting because you can’t go back and fix anything,” he stresses. That’s what, in his opinion, makes ELASTOSIL® M 4630 A/B so suitable: it does not exhibit any chemical shrinkage, and so does not contract. The result and the quality of the work are not visible until the model is removed from the mold, however. “Cast models generally last longer and retain their quality better than copies made vertically,” the Frenchman explains, running his hand through his close-cropped hair after finishing the job.

“You can’t make any mistakes while casting because you can’t go back and fix anything.”

Arnaud Briand, moldmaker and plaster-caster, Meilleur ouvrier de France (2015)

The master craftsman, who bears the title of Meilleur ouvrier de France, blends the silicone. He knows the formulation by heart and adjusts it to suit the current room temperature and humidity.

Dozens of copies possible

If it never comes into contact with water, a plaster cast can last for up to 1,000 years, Briand explains. And a silicone model? “We can’t say for sure, since we’ve only been using the material for 50 years.” It also depends on how often a copy is cast from the mold. “We’ve used a lot of our molds here 30 to 40 times. Others we’ve only used once.”

The greatest demand, he says, is for sculptures of Molière and Voltaire, and the bust of Louis XIV by sculptor Gian Lorenzo Bernini. “Bernini is one of my favorite artists. He was a contemporary of Michelangelo, but in my opinion, Bernini’s work is even greater than Michelangelo’s. His sculptures display extraordinary finesse.”

At the end of his workday at the “Ateliers de moulage,” Briand is covered head to toe in white flecks of plaster, silicone and resin droplets. The floor, work benches, tools – simply everything in his studio – is spattered with spots. Only the sculptures gleam in flawless white.

Does he have a project that he dreams of doing? The father of two does not hesitate for long: “The best projects are always the ones you haven’t done yet,” he says as he leaves, closing the studio door behind him. Its silent residents, the hundreds of busts and sculptures, now wait for their latest companion – created today by Arnaud Briand’s hands – to leave the drying chamber and join them on the shelf.

A finished mold: a number of layers combine to form a solid casing. In the center, you can see a negative impression of the back of a sculpture.